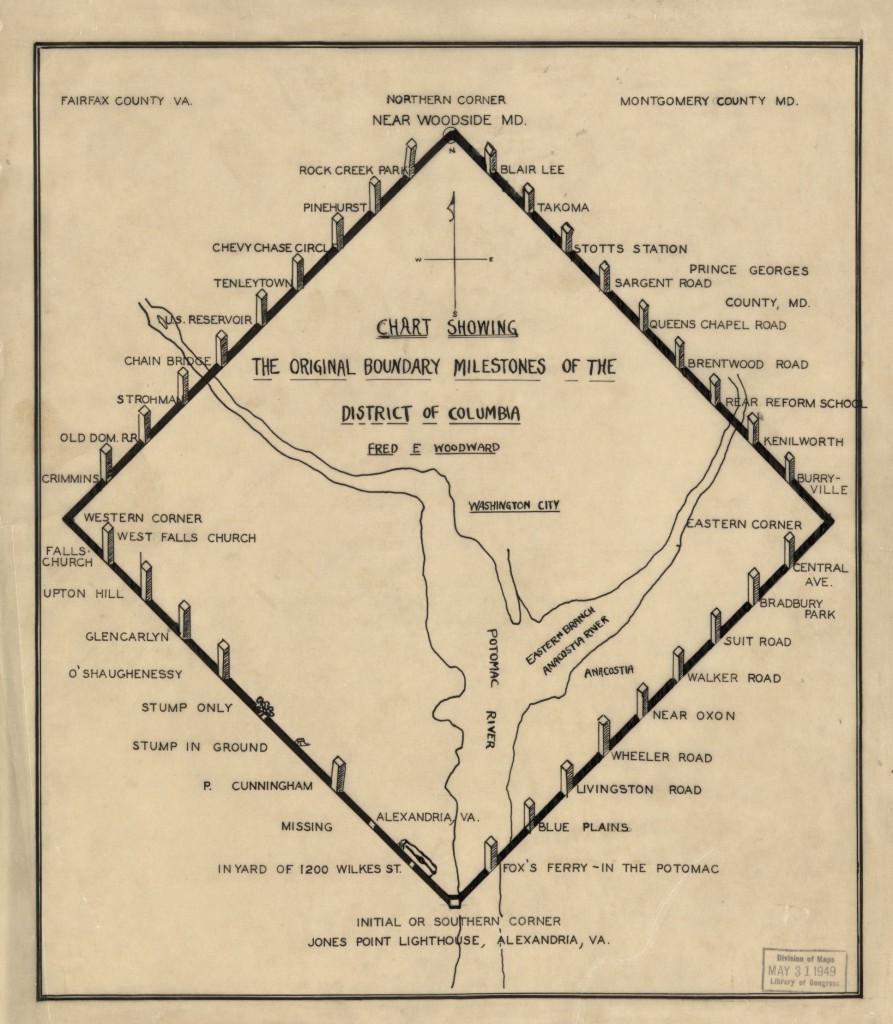

This is the story, borrowed from the extensive research done at www.boundarystones.org, which explains the history behind the nation’s “oldest federal monuments,” the Boundary Stones. Included are the locations of the stones in or nearest to Arlington County. Many of the over 200 year-old markers can still be visited and we recommend a visit to the website as well.

“The Residence Act of July 16, 1790, as amended March 3, 1791, authorized President George Washington to select a 100-square-mile site for the national capital on the Potomac River between Alexandria, Virginia, and Williamsport, Maryland. President Washington selected the southernmost location within these limits so that the capital would include all of present-day Old Town Alexandria, then one of the four busiest ports in the country. Acting on instructions from Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Major Andrew Ellicott began his initial observations for a rough survey of the ten-mile square on Friday, February 11, 1791.

Ellicott, a prominent professional surveyor, hired Benjamin Banneker, an astronomer and surveyor from Maryland, to make the astronomical observations and calculations necessary to establish the south corner of the square at Jones Point in Alexandria. According to legend, “Banneker fixed the position of the first stone by lying on his back to find the exact starting point for the survey … and plotting six stars as they crossed his spot at a particular time of night.” From there, Ellicott’s team embarked on a forty-mile journey, surveying ten-mile lines first along the southwest line, then along The northwest line, next along the northeast line, and finally along the southeast line. The team completed this rough survey in April 1791.

On April 15, 1791, the Alexandria Masonic Lodge placed a small stone at the south corner at Jones Point in ceremonies attended by Ellicott, federal district commissioners Daniel Carroll and David Stuart, and other dignitaries. George Washington did not attend the ceremony, although he did visit the site the prior month. Newspapers around the country announced the story of the beginning of the new federal city. (In 1794, the ceremonial stone at Jones Point was replaced by a large stone, still in place today, with the inscription “The beginning of the Territory of Columbia” on one side.)

Ellicott’s team, minus Banneker, who left after the placement of the south stone, then began the formal survey by clearing twenty feet of land on both sides of each boundary line and placing other stones, made of Aquia Creek sandstone, at one-mile intervals. On each stone, the side facing the District of Columbia displayed the inscription “Jurisdiction of the United States” and a mile number. The opposite side said either “Virginia” or “Maryland,” as appropriate. The third and fourth sides displayed the year in which the stone was placed (1791 for the 14 Virginia stones and 1792 for the 26 Maryland stones) and the magnetic compass variance at that place. Stones along the northwest Maryland boundary also displayed the number of miles they fell from NW4, the first stone placed in Maryland. Stones placed at intervals of more than a mile included that extra distance measured in poles.

The boundary stones are the oldest federal monuments. Although several stones have been moved or severely damaged, thirty-six stones from the 1790’s are in or near their original locations, including all fourteen in the land that was returned to Virginia in the 1846-1847 retrocession. Three other locations have substitute stones (SW2, SE4, and SE8), and one location (NE1) is marked only by a plaque. This site describes the locations of the stones as of 2016, updating the information provided by the Daughters of the American Revolution (1976) and the National Register of Historic Places (1996).

SW1 1220 Wilkes Street: SE corner of the intersection of Wilkes and S. Payne Streets in Alexandria, Virginia. Around 1904, the stone was moved 225 feet from its original position. When it was reset in the ground, it was rotated such that the sides of the stone marked “Virginia” and “Jurisdiction of the United States” no longer face their respective jurisdictions. The letters on the District face of the stone are smaller than those of the other stones and in a different script.

SW2 7 Russell Road: east side of Russell Road just north of King Street. This is neither the original stone nor the original location. Baker and Woodward reported the original stone to be missing as of the late 1800s, and DAR records show that the current stone was placed at this location in 1920. The original stone was located about 0.35 northwest of this replacement. According to Woodward, the original “stone was evidently placed on the east side, and very close to, [King Street], on the eastern side of Shuter’s Hill, in a subdivision” now called Rosemont.

SW3 2932 King Street: north end of parking lot of the First Baptist Church, south of Scroggins Road in Alexandria, Virginia. This stone has been removed from the ground and reset in concrete. Note that the address is not 2952 King Street, as some sources state.

SW4 Adjacent to Fairlington Village at the edge of east side of King Street between S. Wakefield Street and Route 395. According to Woodward, farm plows had destroyed the top of this stone by the early 1900s. After being repositioned when the highway was widened, the remaining portion of the stone has sunk very low into the ground.

SW5 North side of Walter Reed Parkway 100+ feet east of intersection with King Street. Only the stump of this stone remains. Its current condition is consistent with Woodward’s 1908 report that the “stone is broken, and the top seems to be lost. The entire base, with a few inches of the finished portion, was found lying on the ground in approximately the same spot where it had originally been placed.” This stone is now nearly 45 feet from its original position.

SW6 Median strip of Jefferson Street 0.1 miles south of Columbia Pike in Arlington, Virginia. This stone has been repositioned several times. It also has been hit by a car and cemented back together.

SW7 5995 5th Road [South], Arlington, Virginia: Carlin Springs Elementary School, parking lot C, near the fence. It is also possible to reach this stone from the opposite direction via the private park behind the tennis courts at 3101 S. Manchester Street, Falls Church, Virginia. Follow the southeast edge of the tennis courts to the (often locked) gate to the private park.

SW8 A short distance from the intersection of John Marshall Drive and Wilson Boulevard: 100 feet southeast of water tower behind the Patrick Henry Apartments. The stone is at the edge of the parking lot across from units 6184 and 6172. As the informational sign near the stone states, this is not the original location.

SW9 Benjamin Banneker Park on Van Buren Street south of 18th Street in Falls Church, Virginia.

WEST Andrew Ellicott Park: 2824 N. Arizona Street (sometimes listed as 2824 Meridian Street), south of West Street in Falls Church, Virginia.

NW1 3607 Powhatan Street, north of 36th Street in Arlington, Virginia: west side of back yard, 200 feet from the road.

NW2 5298 Old Dominion Drive or 5145 N. 38th Street, Arlington, Virginia: in the fence separating the back yards of two homes.

NW3 4013 N. Tazewell Street, Arlington, Virginia: back yard of home.”